|

For this year in Advent, our church is reading through the contemporary Advent Collects in the Book of Common Prayer. The Book of Common Prayer is a literary tradition spanning back to the time of the Reformation. It was a powerful tool that the Anglican Church used to shape its people around Christ. Not quite a hymnal, but similar, the Book of Common Prayer was valuable as many saints from all around the world forsook the world, the flesh, and the devil and sought to make their lives look more like Jesus using this book. We are not an Anglican Church, and we are not Anglican for some very important reasons. However, we do believe that, as far as this particular tool adheres to the Holy Scriptures, it is valuable for us to grow into Christ's image. So for the month of December, I am going to be blogging on the various readings from the Sunday Readings, called a "Collect." Each of these Collects is a prayer around a particular theme of Christmastime. The first one is a prayer that is shockingly eschatological (meaning it is about the end times). It is draped in the imagery of war and of the end times. Of that troubling and turbulent time to come, and of the peace which is on heaven and earth, good will to men. The peace of God only comes through the invasion of Christ. Needless to say, this is not your grandmother's Christmas! It reads as follows:

This first, this first prayer, has three important sections to it. First, it has the present. Second, it places the present in light of the eternal. Third, it pleads on the basis of the Triune God. Let's deal with each one in turn. Almighty God, give us grace to cast away the works of darkness, and put on the armor of light, now in the time of this mortal life in which your Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility The first prayer of the Collect is a request for God to give us the grace of repentance. This is given a vivid flare by the contrast of darkness and light. We are invited through the Collect to ask God for grace to the task to be done. Christmastime, we learn, is not a time for pithy sentimentalisms. It is a time for war, a time when we embroider ourselves with the blood of the lamb. We desperately need the grace to fight this battle well. We need the armor of light, for the task at hand. This war requires work. This war is the most recent flare up of an eternal battle. And the campaign was started when God the Son paradropped into the sleepy town of Bethlehem. But the Son did not come as a mighty warrior, clothed in strength and armed with power. No, he came as a low-class carpenter, swaddled in the flesh of a babe. So great is this conquering Lord, that he will gather to himself those who come to him as his Son came to earth: the hesitant and humble, the bashful and bedraggled, the forgotten and forsaken, the unloved and untouched. He will carve his image into this forgotten stone of human misery. The chief weapon of Christmas war, we see, is the humiliation of God in the flesh of man. that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious majesty, to judge both the living and the dead, we may rise to life immortal Of course, this one who conquers through being killed, who defeats through death, who overthrows every power and name by being born in a backwater corner of a backwater province of the Roman Empire, will not come a second time so. Rather, the one who was born, lived, died, rose again, and ascended, will return on high. And when he does, he will gather himself the army of outcasts, and they, this messy mob gathered from the corner of every slum there ever was, will become as he is. At Christmastime, we look forward to the glory to be revealed in us. The glory of the angels on high, sweetly singing o'er the plain, will one day be ours! No longer will we have sunken cheeks, canyons formed by the everflowing saline springs in our eyes, the bony arms, and look of those who are in a world not their own. Rather, we will have glorious majesty, life immortal, raised with the resurrected and ascended Lord. Christmastime is when we look at that manger, the place where the sheeps and the goats feed alike, and we see the Lamb standing as though he had been slain. through him who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen. The final stanza of this first prayer carries us into the eternal plan of the infinite, triune God. The humble will be come the high, the meek the majestic, the gentle the glorious. We who carry in our flesh the cross of Christ will burst forth in glorious day. But this only happens through the one who was humble to the point of death, who was meek to the point of flagellation, who was gentle as a lamb led to the slaughter. And this, this is what we celebrate at Christmas. The advent of the Son of God, conceived by the Holy Spirit, commissioned by His Father, sent from the foundation of the world, and who will one day rule over the world. The Triune God is the God of Christmas Time, he is in it and through it and with it and for it and against it all at once. The Lion of the Tribe of Judah comes to us as the Lamb of Bethlehem, that sleepy shepherd town.

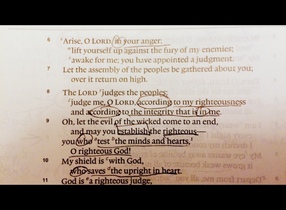

And nothing would ever be the same.  In America, we celebrate the holiday of thanksgiving once a year. We eat turkey, we watch football, we take time off. We dub this regimented indulgence, "Thanksgiving." We trace the tradition of yearly Thanksgivings specifically to our first fathers and mothers who came across on the Mayflower, but also through the presidency of Abraham Lincoln who instantiated the holiday of Thanksgiving. Well and good. Of course, how the practices of Thanksgiving actually relate to the command of God to be disciplined in giving thanks (Psalm 147:7) is something of a conundrum. We engage in the practice, but think little about the tacit formation. What does it mean to practice thanksgiving? Are our yearly practices of Thanksgiving actually congruent with the Scriptures' command on us to give thanks? To practice thanksgiving requires at least two steps. 1 - It is to acknowledge that everything that we have is from one another. This requires a pain-staking humility. To truly give thanks, we must come to an end of ourselves. We must look to something we have which we could not have attained for ourselves. Thanksgiving is the discipline where the gifted gratefully reflects on the gift the giver gave him which he could not have given himself. In other words, it requires us to say, "This came from someone else. It is gratuitous." The theoretical reason food is associated with with gift giving is an acknowledgement that that sustenance comes from another. We indulge in a whole array of foods and fill ourselves, and after we wake up from our food coma, we recognize that we could not have achieved that on our own. This is why we pray with thanksgiving at the beginning of every meal. It is to recognize that this comes from somewhere else, not ourselves. We recognize all that God has given us, all that God has showered on us and lavished on us. We recognize it is totally undeserved. It is not something we did to deserve it. This is the step that most people feel comfortable with. 2 - It is to reflect on what this implies about the character of the giver. If the giver gave the gifted such a gift, what does that imply about the giver? This is the step we don't care for. We don't take this step of thanksgiving first, because it requires work, and second, because the results can be somewhat disconcerting. For example, if I have much on my table, it is easy to give thanks. How generous this implies my God is! How wonderfully this compels me to think of him! But when all that is in my cornucopia are crumbs of stale bread or scraps of singed meat, what does this imply about God? That he has a purpose in my pain? I don't want to think about that. It is easy to give thanksgiving on Thanksgiving, or even on Christmas. We can be thankful even then. But in January, when the sky is glum, the ground is wet, and the table is empty? Can we be thankful even then. Can we believe that God would use even those seasons in our lives, where we are lean and hungry, trembling and tired? The discipline of Thanksgiving teaches us to be so. This might be a difficult practice to wrap our minds around. Yet it is essential. Because, Thanksgiving teaches us how to come to our Savior. When we come to him, all our Thanksgiving emotions point every direction (Rev 7:12). Because when we see him crucified, shamed, emaciated, skinny, ugly, ghoulish, bloody, broken, bruised hanging on the cross, what does this imply about God? Can we give thanks, even for this? Yes, we can admit, we could not provide a sacrifice on our own, the gift for the gifted is not of himself. But can we admit that this is the God who does indeed provide? A sacrifice for our sake. A broken body for ours. A man estranged in our place? Indeed it is He. But we also see a lamb, standing as though it were slain. Not only has he been killed, he has also been enlivened. Not only has he been crucified, he has been resurrected. Not only was he lowered into the ground, he is risen. When we give thanks for this, the greatest of gifts, we recognize that this too, this is our God. The God who provides. The God whose gift is not only death, but also life. Not only darkness, but also light. This thanksgiving, whether with plenty or little, with full or empty plates, give thanks to this God. The God who gave one to die for you, and gave one to life for you. The God who gave the lamb who is standing though he has been slain. Come to an end of yourself, and there you will begin to come to Him. "Nothing in my hand I bring, simply to the cross I cling."  One of the books that I am currently reading through is my friend John Dickerson's, I Am Strong. I love what he says about prayer: The disciples knew where Jesus got His power. It was through prayer. That's why they made this request of Him: "Lord teach us to pray" (Luke 11:1). They weren't being religious when they asked for the prayer lesson; they were being hungry. They wanted the same power Jesus had. If you think of the lengthy prayers that preachers, politicians, and leaders bellow out with their eyes half closed, it's comical to note the brevity of Jesus' model prayer. No fluff or pomp. No chest beating. The entire pinky of a prayer folds into two easy halves: 1. Jesus aligns Himself with the father. 2. And then Jesus asks. That's it, He aligns. And He asks. Quite specifically, quite gutturally, with vulnerable unveiling, He asks. (Dickerson, I am Strong, 60) I have always loved John's writing style, but this really caught my attention. It is a helpful approach to prayer: Align ourselves with God's will, Ask. I think this fits neatly into the language of Union and Communion with Christ. Our Union with Christ is the objective, once for all, inclusion into the death and resurrection of Christ and participation in the benefits He acquired through them. Through our Union with Christ, we are dead and buried because Christ is dead and buried (Rom 6:1-4). We are justified because Christ is justified (Rom 5:25). Because Christ is holy we are holy (1 Cor 1:30). To be in Christ is to give him all of our sin, all of our shame, all of our guilt and to receive all of his righteousness, all of his honor, and all of his right standing before the Father. In Christ we are no longer at war with God, but at peace with Him. In Christ we are no longer condemned, but we are justified. In Christ, we are no longer slaves of sin, but we are redeemed. In Christ, we are no longer estranged, but we are reconciled. Because Christ is a son of God, we who are untied to him are adopted into the family of God, so that His Father becomes ours. It is this union with Christ that we align ourselves so deeply with when we pray. We, "step into" our union with Christ to experience all that he has for us from the Father. We are not coming to the throne of the Father as childless orphans or servants plucked from some dungy corner of the house, we are a royal people availing ourselves of our royal privilege. We are the sons and daughters of the King. But we are also not pedestrians or citizens of another fiefdom. We have responsibilities and we exist for the interests of the King. We pray ultimately in the name of Christ and for the will of the Father. Being the sons of the King, we carry his standard rather than our own. We have both rights and responsibilities as the children of God. To align ourselves in prayer is to put on this royal identity, it is to "put on Christ." (Col 3:10) But prayer is more than just "aligning." It is also asking. To ask means to give voice to that murmur that restlessly travels to and fro on the watery surface of our hearts. It is to allow that voice that rustles the leaves of our hearts out. It is to bring to God every worry, every concern, every anxiety the we have, and to trust that He will hear, and He will answer in His own way and in His own time. And that answer will be a good answer, because He is good. This is the most sonly or daughterly thing you might do today: to reach out to God in prayer and to be honest with Him. This might be the most heavenly thing you do today: pray to your heavenly Father. I love what Helmut Thielicke says about this: "A child who prays to the loving God for a hobbyhorse or for good picnic weather makes fools out of these wise men. With his little hands he points to the greatest good, the heart of the heavenly Father. " - (Helmut Thielicke, I Believe, 41) This is what it means to align and to ask. To have union, and to commune. To be adopted by God, and to petition to God. This is the Christian approach to prayer.  - Pastor Matt LaMaster - He stood up, waving his hands. Those hands, calloused with the workman’s trade, were once instruments of kidnappings, beatings, and torture. Now they did little to shield him from the same blows directed at him. A strange reversal had happened, and now the man faced the same mob he once led. He opened his mouth to speak. For everything we know from his writings, Saul of Tarsus’ life remains dim. What is best preserved for us is the beloved doctor Luke’s commentary on his life between his conversion and his first imprisonment in Rome. Much of the rest of his life is obscured, although there are clues. Saul, we know, was from the port city of Tarsus, a hub of Mediterranean activity, being the gateway to Galatia and other regions in Asia Minor. He grew up in a home with some semblance of religious tradition, after all they still knew their tribal roots, a rarity for Jews in that day. And yet, despite this, Saul’s parents raised their son to know Greek. They were wealthy enough to buy Roman citizenship, a prized status in the eyes of the migrants in the Roman empire. It was their sign that they had “made” it. To say the least, this Benjamite clan had settled with the way things were being done by Rome with complete satisfaction. They were likely Hellenistic Jews, moderate and nominal. Somewhere along the way, young Saul radicalized. Perhaps it was on a pilgrimage to the holy city. Did he run away from home? Maybe it was on a visit to relatives in Jerusalem. The details are obscured, after all, Paul counted everything before his conversion as rubbish (Phil 3:8). The Saul we know was a likely dedicated religious scholar throughout his twenties, training under the influential post of Gamaliel. Perhaps Saul was his protege. No longer a Hellenist, Saul had made the dip into pure Judaism. He adorned himself in the law, becoming blameless. The funny thing about beliefs, though, is that they matter. They really matter. This is why when a rabbi with the outlandish message that he himself had come to reveal God, that he in fact was God, the very Word by which the world had been brought forth, a fire was lit under establishment’s feet. This fire, which was running amok (even in Samaria!) had to be stamped out. For this quest, they needed a zealous young Jew, who better than the up-and-coming Saul? We have gotten too familiar with the text to realize the enormity of Saul’s actions, and his brash rebellion. Saul approved of the mob that killed Stephen, he sanctioned the action with the authority of the religious establishment, holding the coats above the ground, to keep the mob clean from the dust of the beaten path (Acts, 7:58, 8:1). Saul gladly overstepped the legal restraints the Romans had placed upon Jews. Saul ravaged the church (8:2). We seem to forget that he went from door to door, kidnapping women, children, and men who had called upon Jesus Christ. This was not a legal procedure. This was a man who wanted to force the kingdom of God. He wanted to set up the heavenly abode, and he was willing to slaughter whoever stood in his way to do it. He was embroiled in sectarianism. He was zealous for his religious identity. Saul’s quest to Damascus was to kidnap Christians. Are we really to imagine the authorities of his day would have been pleased with his actions? There was a shred of formality to it, in the same way Al-Queda has affiliates, or ISIS has a ruling council. Let us not believe this to be a benign violence, this was the equivalent of terrorism. This is the extent to which Saul felt threatened. For the message of grace threatens the self-righteous. And the reaction of the self is violent. Saul’s life, his convictions, everything he was, had been dedicated to becoming blameless under the law. So zealous was he for this law-serving lifestyle, he would willingly put his life at risk to prove it right. If anyone had come to know the righteousness the law gives, it would have been him. And then a funny thing happened. God saved him. Jesus Christ met him on the way to Damascus. Lights flashed, sound boomed, and everything went dark. The judgment of the Almighty had been pronounced on this self-styled Pharisee, and despite all his law-keeping, he was found wanting. From that moment, Saul became Paul. The persecutor became the persecuted. The carrier of death became the herald of life. The Jewish zealot became the apostle to the Gentiles. The self-righteous became justified. The one who was so cold and darkened was in an awful instant united to the Lord Jesus Christ. The one born wealthy took up a blue collar trade to support himself so that he might gospelize the nations. Now as he stood before this very mob decades later, with his hands motioning, he explained to them what had happened. That day on the Damascus Road, Saul, perhaps with a tremor in his voice, asked Jesus Christ what he must do. Paul wanted to earn forgiveness from Christ, to do penance. The Lord sent him to a pious believer named Ananias who restored to him his sight, and ordered him to be baptized (Acts 22:6-15). Notice the pattern, the Lord first restored his sight and then gave him instructions to be baptized. There was nothing to really do. He had asked the Lord what he might do, and he had found this to be the secret of the Christian life; there really is nothing to do, just someone to know. There is nothing to earn, only someone to receive. Of course there are good works which we have been transformed for (Eph 2:10), but these in themselves are diving deeper and deeper into the one who has created us, and they call us back to him, they are the fruits of our union, not a way we purchase salvation. Saul had grown accustomed to earning a right standing before God, and now it was proffered in the scarred hands of the object of his hate. And in grasping those broken, mangled, bloody hands, he found himself healed. After all his strivings he found rest. At the bottom of it all, you and I are not so separate from this disparate man or the thousands other like him. You and I all search for meaning and purpose in our own pithy systems. Let each of us reckon that our strivings are as Paul's. You and I are an extremist in the same way. Perhaps our systems are less externally vitriolic and more polite, in a Victorian kind of way. But, make no mistake, when our self is threatened it lashes back just as violently. Like Christ, everything before Christ is nonetheless rubbish. Will you see Paul's hands waving in the wind? Will you grasp Christ who beckons you to himself? Blaise Pascal says it well in his famous Pensèes, “It is good to be tired and wearied by the vain search after the true good, that we may stretch out our arms to the Redeemer.” May this be so for you and I.  A lot of people think that reading, understanding, and applying the Bible is something for leaders (pastors, professors, elders, small group leaders) but not for me. This is a pretty common attitude, and sometimes, unfortunately, it's perpetuated by well intentioned leaders or some with an inflated sense of their own importance. But God has made his Word available to all his people, not just the leaders of the church. Howard Hendricks sets out 3 simple steps for good Bible study that everyone can do in his book Living by the Book. It's helpful to think of these as 3 "buckets" to put your questions about the Bible into. Here they are: Observation: Make as many observations about a passage as you possible can. Ask questions like these:

Interpretation: Try to understand the meaning of this passage that is behind all the details of the passage:

Application: Try to find specific ways to apply this passage to your life.

|

Southern Heights Christian ChurchCome here for thoughts on how to follow Jesus in our every day life! Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

Telephone |

Address5401 Madison Ave

Anderson, IN 46013 |

ServicesSunday School :: 9 AM

Sunday Service :: 10:30 AM |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed